With his wavy locks and hard-ass goatee, Brian Crecente brings a venturesome, tremendously Zorro quality to games journalism. As Managing Editor of Kotaku, our paths tend to cross alot. He's good people, and I was curious what he'd have to say on this week's topic. Turns out he's kind of a poet. - (CW)TB

Digital Rights Management is gaming’s own little Ouroboros: A snake in the grass consuming itself, a seemingly endless problem without beginning, end or solution.

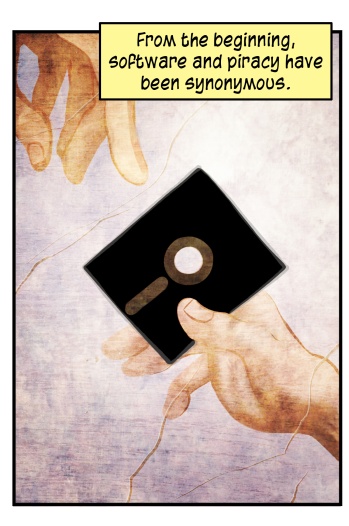

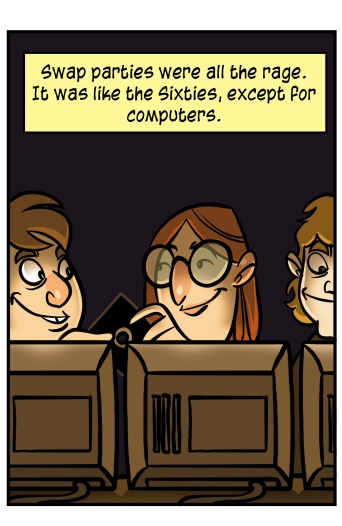

As long as there are creative works people will want to buy them, protect them and, yes, even steal them. Even this modern use of the word piracy dates back to the 1700s when Daniel Defoe agonized over hand-written, pirated copies of his poems sold on the streets. He called those erstwhile literary thieves "pirates" and "paragraph-men."

Imagine, though, an unsuspecting bibliophile returning home with their copy of The True-Born Englishman only to discover that once they’ve read it, the pages turn to ash. Or maybe they can read it and let a couple of friends borrow it, but that’s it. No more reads, thank you very much. What if they find that there is someone lurking outside their library window, watching them, making sure no one else catches a glance of page 32? Or, god forbid, they try to go and sell the book back?

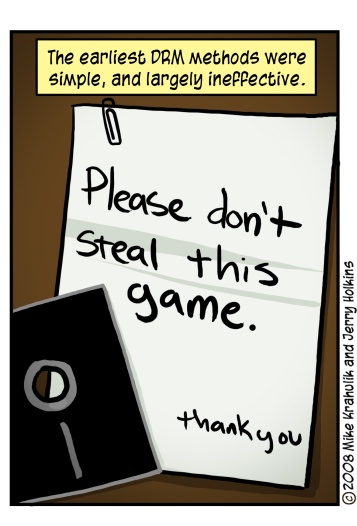

No, copy protection in the 18th Century was a much simpler thing. There was no technology to obfuscate what a publisher was doing. No ghosts in the machine. No machines. But today, as the ways a game or creation can be stolen increases, so do the little lies, the hidden spies created by those creators.

SecuRom is just the latest set of golden handcuffs given out free of charge with every copy of a game purchased. We find it lurking in Bioshock, in Mass Effect, in Spore. It ties up the thing purchased in an invisible web of restrictions, telling gamers how they can game, and what they are allowed to do with it once finished. It also turns the most honest of gamers into a potential thief, a suspected pirate and program-man.

Most recently Electronic Arts ran afoul of the backlash created by such restrictions and preemptive labeling when they included a version of SecuRom in Spore. But they quickly capitulated to a tidal wave of unrest and gamer angst, saying that they would free up the usage of the game, cut some of those webs, allowing gamers to install it five, not three times. They also plan to allow gamers to deauthorize a computer, the way Apple does with iTunes.

Perhaps, as they confront this second wave of gamer controversy, EA will pull the plug on SecuRom all together. But to do what, replace it with another tiny spy? Perhaps we could call it SafeDisc or StarForce or Tages. No, I think the solution can only be found if gamers, developers and publishers work together to create a thing of least evils.

Personally, I think a good starting point is a system like Steam, Valve’s digital distribution and security system. The software was horribly broken when it came kicking and screaming to life during the abortive launch of Half-Life 2. But over the years Valve plugged away at the software, turning it into something that has at least a kernel of gamer interest at its heart.

Developers and publishers have the right to protect their interests, to ask that I pay for what I play. But don’t we have the right to own what we’ve purchased? To do what we want with it? Are we buying games, or renting them? The industry needs to meet us halfway. This is a problem that hurts everyone, both in its repercussions and its current solutions.